Guiding questions on language assessment

1) What is the objective in assessing the language competence of my learners?

The objective of conducting language assessments at schools can be divided

into two main categories: selection and

support.

Assessing language competences for selection purposes often takes place during

key transitional periods. For example, a school may wish to assess students in

order to place them in specific classes, streams, groups or tracks. Therefore,

the focus of the assessment is to identify deficiencies in the student's

skills. The results of this type of language assessment are not used to

support students’ language competences, but rather to support institutional

decisions. This can have a negative impact on bilingual children. If

assessment separates students from “powerful, dominant, mainstream groups in

society, the students may become disempowered” (Baker 2006). This can lead to

classification and marginalisation.

Using assessment for support purposes means focusing on students’ competences

and this requires a different approach to recording individual learner

profiles. In this case, the results of the language assessments are used to

determine difficulties in language development and to generate individual

support. Ehlich declares language support as the main objective of assessing

language competences (cf. Ehlich 2007).

Assessments should take place regularly and early on in the school career, so

that difficulties can be addressed, support measures validated and new goals

set at frequent intervals.

For students in higher grades, it is important to assess competences relating

the educational language. This demonstrates whether the students are able to

follow lessons and whether they need more support during the transition

between the common language and the educational language phases.

A third objective for assessing would be for

research purposes.

2) What has to be taken into account when assessing plurilingual learners?

It is important to differentiate between monolingual and plurilingual

students. If the performance of plurilingual students is compared

undifferentiated with the performance of monolingual students, there is a risk

that the results will be misinterpreted.

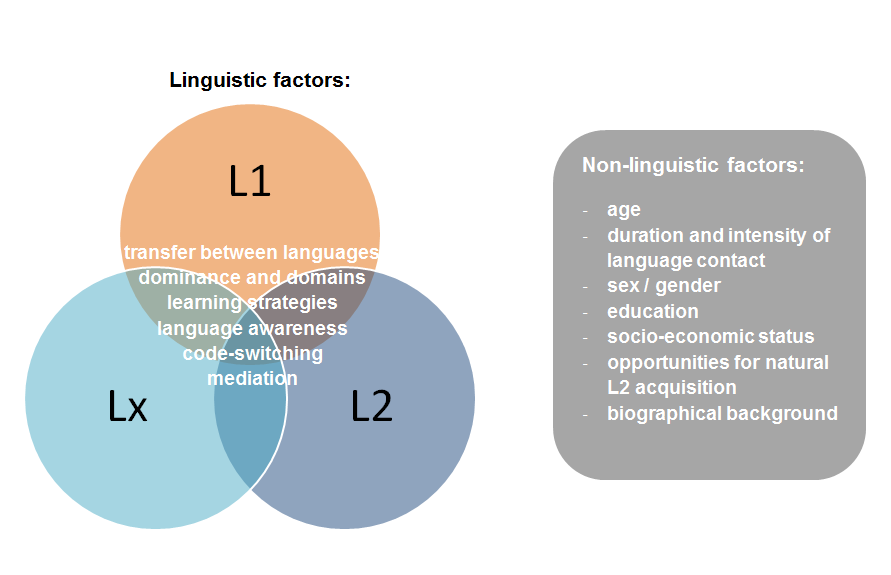

When plurilingual students are assessed, it is important to consider three

aspects of their development : 1)

first language proficiency; 2)

second language proficiency; 3) the existence (or not) of a

physical, learning or behavioral difficulty.

For an adequate interpretation of assessments, it is also necessary to give

greater consideration to the first language, the duration and intensity of the

language contact and other factors (cf. Reich 2007). Baker emphasises, arguing

that students’ ability to function in a second language must not be seen as

representing their level of language development. Their development in the

first language needs to be assessed so as “to paint a picture of proficiency

rather than deficiency, of potential rather than deficit” (Baker 2006).

Furthermore, social, cultural, family, educational and personal information

needs to be collected to make a valid and reliable assessment, and to make an

accurate placement of the child in mainstream or special education.

However, most of the instruments for assessing language competences do not

consider these factors. Furthermore, if they are used, it is important to

point out that the assessment has been carried out only for the language of

schooling and is therefore incomplete, as it doesn’t take into account the

first language.

The following image illustrates factors that affect the second language

acquisition of plurilingual students.

- References: Ehlich (2005); Gogolin/ Roth/ Neumann (2005); Image: Antje

Aulbert

3) What linguistic skills do I want to assess?

Language is a form of human action because it is a form of communication

between a speaker and a listener. To become proficient in this type of

communication, it is necessary to acquire a complex range of linguistic

skills.

In order to illustrate the dimensions of a range of language skills and how

they are related, Ehlich developed the

concept of basic linguistic skills

(Ehlich 2005). Despite the fact that these skills are described separatelly,

it is necessary to think of them as a whole. A person doesn’t acquire these

skills consecutively, but simultaneously. The different skills are linked to

each other and in actual speech, work together. However, when analysing these

skills, in order to identify the dimension in which this collaboration does

not work for an individual, it is useful to separate them systematically (cf.

Prestin/ Redder 2011).

Take a look at an overview of the

basic linguistic skills.

4) What language requirements does school put on the learners?

School enrolment provides specific challenges for plurilingual students. At

the time of enrolment, statistics show that children with a migrant background

have a considerably smaller vocabulary compared to monolingual German children

(cf. Ahrenholz 2010). This means that many plurilingual students have to catch

up in terms of basic vocabulary at the same as they have to learn

school-related vocabulary. This lack of vocabulary cannot be addressed without

adequate support and can lead to difficulties in reading and writing (cf.

Esterl/Struger 2011).

Another challenge relating to enrolment is difficulty in acquiring the

standard language, which accounts for an increasingly significant part of the

language of schooling. In the first years of elementary school, the target

language is more simplified, which is why the difficulties of plurilingual

students often are not discovered (cf. Cummins 1984). In higher classes, the

technical language is more important as it is a receptive and productive

component of the lessons. If the terminology is not acquired sufficiently,

lesson participation gets more and more difficult (cf. Ahrenholz 2010).

Cummins expressed the distinction between different language requirements in

terms of basic interpersonal skills (BICS) and cognitive/academic

language proficiency (CALP). He defines BICS as the

skills that are needed in social situations. They are used

when there are contextual supports and props for language delivery. For

example, face-to-face “context embedded” situations provide non-verbal support

to secure understanding. CALP is essential for students

to succeed in school. Academic language acquisition includes

skills such as comparing, classifying, synthesising, evaluating and

inferring. Academic language tasks are context reduced. Information

is read from a textbook or presented by the teacher. As a student gets older

the context of academic tasks becomes more and more reduced (cf. Baker 2006).

Watch a

video

of Jim Cummins explaining the importance of and differences between BICS and

CALP.

5) What resources do you have access to? What other resources would be useful?

The aim here is to think of all the resources that facilitate language

assessment. Resources should be considered in terms of time (how much time do I have for

assessing?); staffing (do I get support from

external experts, e.g. language advisers? Can I get help or information from

other teachers at school?); materials (what assessment

instruments do I have access to?); and finances. Furthermore,

what resources should be considered in relation to

teacher training and further professional development.

References:

-

Ahrenholz, Bernt (ed.) (2010): Fachunterricht und Deutsch als

Zweitsprache. 2. Auflage Tübingen: Narr. S.17ff

-

Baker, Colin (2006): Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism,

4th Edition. Multilingual Matters. pp: 358, 362, 352.

-

Ehlich, Konrad (2007): Sprachaneignung und deren Feststellung bei Kindern

mit und ohne Migrationshintergrund: Was man weiß, was man braucht, was man

erwarten kann. In: BMBF 2007. S.50.

-

Ehlich, Konrad (ed.) (2005a): Anforderungen an Verfahren der regelmäßigen

Sprachstandsfestellung als Grundlage für die frühe und individuelle

Förderung von Kindern mit und ohne Migrationshintergrund.

Bildungsforschung 11, herausgegeben vom Bundesministerium für Bildung und

Forschung. S. 98,131 ff. 143 ff.

http://www.bmbf.de/pub/bildungsreform_band_elf.pdf

-

Esterl, Ursula/ Struger, Jürgen (2011): Wort. Schatz-Wörter. Schätzen.

Die: Heft 1/2011. S. 31.

-

Gogolin, Ingrid; Neumann, Ursula; Roth, Hans-Joachim (2005):

Sprachdiagnostik bei Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Migrationshintergrund.

Dokumentation einer Fachtagung am 14. Juli 2004 in Hamburg. Waxmann,

Münster. S. 53 ff.

-

Perstin, Maike; Redder, Angelika (2011): Basic linguistic skills and

linguistic actions. Translated from German. In: Wilmes, Sabine; Plathner,

Franziska; Atanasoska, Tatjana (Hg.): Second language teaching in

multilingual classes: basic principles for primary schools. Eurac

Research, Bolzano: pp 51ff.

-

Reich, Hans (2007): Forschungsstand und Desideratenaufweis zu

Migrationslinguistik und Migrationspädagogik für die Zwecke des

“Anforderungsrahmens”. In: BMBF 2007: S.154.